On the Suffering of the World, by Arthur Schopenhauer (edited by Eugene Thacker)

🖤🖤🖤

Eugene Thacker (professor of philosophy at the New School and author of Infinite Resignation, previously reviewed here) has pulled together a collection of Schopenhauer’s late writings (when Schopenhauer was at his darkest, most lyrical, and most aphoristic), along with an illuminating 55-page introduction to Schopenhauer — his life experiences and their connection (or lack thereof) to the enduring and dominating pessimistic outlook present in all his writings.

More than anything, Eugene clarifies in his introduction the one dominating thought, the throughline through all of Schopenhauer’s diverse works, essays, and aphorisms:

We do not live, so much as we are lived.

We do not exist, so much as we are “existed.”We are at once a part of the world, and apart from the world.

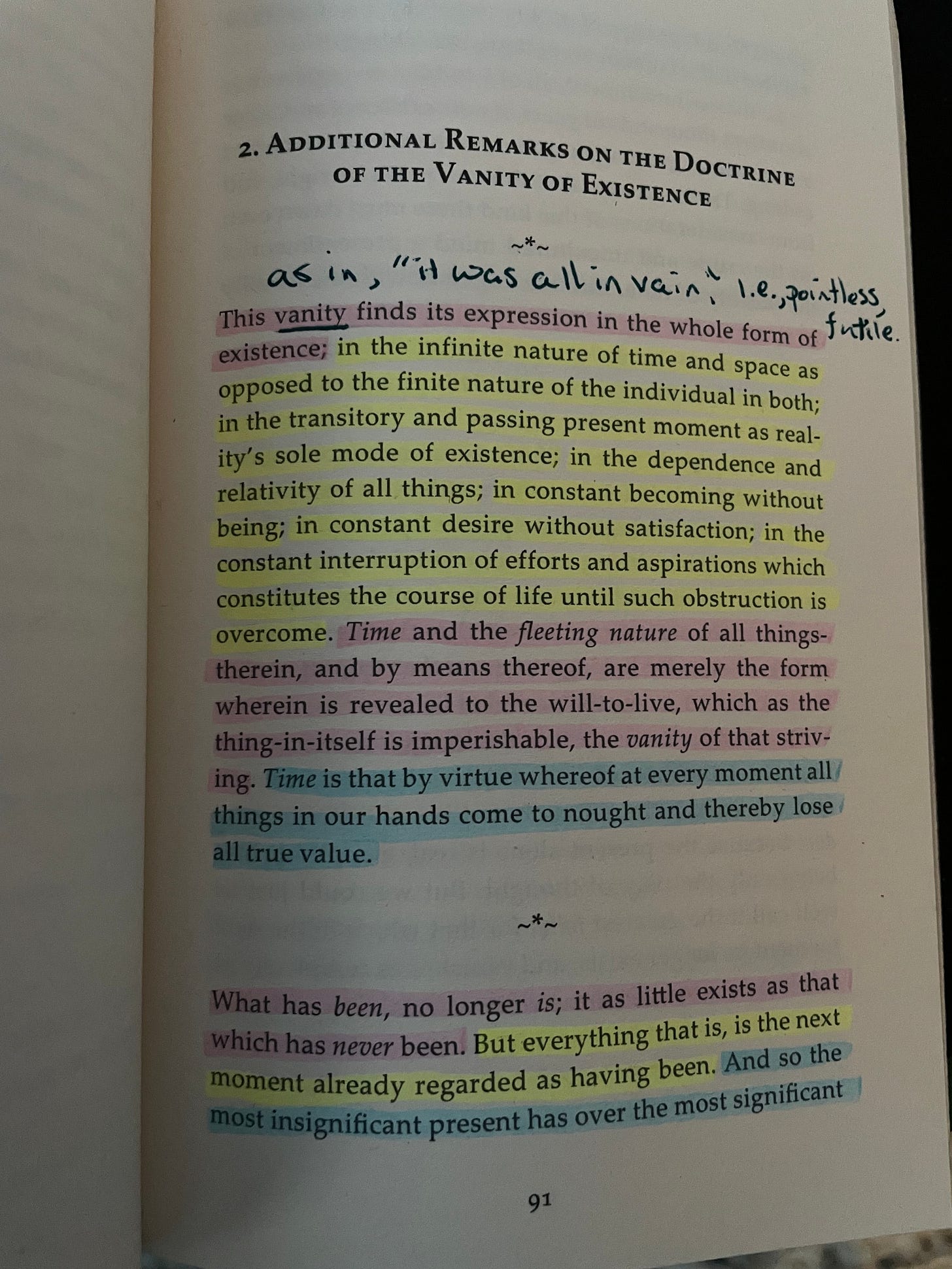

Schopenhauer’s essays in this collection cover the vanity (read: meaninglessness, futility, pointlessness) and suffering of the world, the indestructibility of our true inner nature (the blind, insatiable “Will”), and the pessimistic truths (albeit disguised in myth and allegory) present in the original forms of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Christianity, before they were perverted beyond all recognition by charlatans, demagogues, organized religions, Protestants, etc.

If you’ve never read Schopenhauer, he is well worth the time. At his heights, his prose is blistering in its lyrical frankness:

If you try to imagine as nearly as you can what an amount of misery, pain, and suffering of every kind the sun shines upon in its course, you will admit that it would be much better if on the earth as little as on the moon the sun were able to call forth the phenomena of life; and if, here as there, the surface were still in a crystalline state.

Unlike many philosophers consumed with existential questions, Schopenhauer often writes plainly, and shares the hardest truths to bear:

We can also regard our life as a uselessly disturbing episode in the blissful repose of nothingness. At all events even the person who has fared tolerably well, becomes more clearly aware, the longer they live, that life on the whole is a disappointment, nay a cheat, in other words bears the character of a great mystification or even a fraud. When two people who were friends in their youth meet again after the separation of a long time, the feeling uppermost in their minds when they see each other, in that it recalls old times, is one of complete disappointment with the whole of life. In former years under the rosy sunrise of their youth, life seemed to them so fair in prospect; it made so many promises and has kept so few. So definitely uppermost is this feeling when they meet that they do not even deem it necessary to express it in words, but both tacitly assume it and proceed to talk on that basis.

But despite his reputation as a misanthrope, his writing is colored throughout with empathy and concern:

The conviction that the world and thus also humanity is something that really ought not to be, is calculated to fill us with forbearance towards one another; for what can we expect from beings in such a predicament? In fact from this point of view it might occur to us that the really proper address between one person and another should be, instead of Sir, Monsieur, and so on, Leidensgefährte, socci malorum, compagnon de misères, my fellow-sufferer. However strange this may sound, it accords with the facts, puts the other person in the most correct light, and reminds us of that most necessary thing, tolerance, patience, forbearance, and love of one’s neighbor, which everyone needs and each of us, therefore, owes to another.

His assessment of well-being as negative (metaphysically speaking) and pain as positive is paradigmatic:

We feel pain, but not painlessness; care, but not freedom from care; fear, but not safety and security. We feel the desire as we feel hunger and thirst; but as soon as it has been satisfied, it is like the mouthful of food which has been taken, and which ceases to exist for our feelings the moment it is swallowed. We painfully feel the loss of pleasures and enjoyments, as soon as they fail to appear; but when pains cease even after being present for a long time, their absence is not directly felt, but at most they are thought of intentionally by means of reflection. For only pain and want can be felt positively; and there fore they proclaim themselves; well-being, on the contrary, is merely negative.

But as indicated by Eugene above, the real tragedy lurking behind phenomenal reality is the blind, eternal Will, or will-to-live, conjuring us with its strings:

Awakened to life out of the night of unconsciousness, the will finds itself as an individual in an endless and boundless world, among innumerable individuals, all striving, suffering, and erring; and as if through a troubled dream, it hurries back to the old unconsciousness. Yet till then its desires are unlimited, its claims inexhaustible, and every satisfied desire gives birth to a new one. No possible satisfaction in the world could suffice to still its craving, set a final goal to its demands, and fill the bottomless pit of its heart.

Lastly, if you feel the urge to upbraid Schopenhauer for his bleakness, then heed his retort:

I shall be told, I suppose, that my philosophy is comfortless — because I speak the truth; and people prefer to be assured that everything the Lord has made is good. Go to the priests, then, and leave philosophers in peace! At any rate, do not ask us to accommodate our doctrines to the lessons you have been taught. That is what those rascals of sham philosophers will do for you. Ask them for any doctrine you please, and you will get it. Your University professors are bound to preach optimism; and it is an easy and agreeable task to upset their theories.