This is a 242 page book that could easily have been 2,420 pages. It is well-written, concise, and conceptually dense. Unlike a work of fiction which occasionally throws out a line that gives you pause, this work manages this effect with every chapter, every section, every paragraph, and almost nearly every sentence. Break out your highlighters, pens, and notepads. Do not expect a breezy read.

As someone still early in his understanding of Schopenhauer’s philosophy, I can say that not only did this work elucidate the degree to which Schopenhauer was (and was not) indebted to Kant — to Kant’s (anti)metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, anthropology, and Religionsschrift — it also made clear to me to what extent Schopenhauer’s entire philosophical project is intertwined with his own post-Kantian epistemological innovations. Schopenhauer’s philosophies — his metaphysics, his ethics, his philosophy of religion, his philosophy of art (and artist), his existentialism — all of them stand or fall on Schopenhauer’s epistemology.

Schopenhauer is most famous for his two volume work “The World as Will and Representation”, in which all of his philosophies, not just his metaphysics, are unfolded to greater or lesser extents. However, what is less clear to the initiate is the degree to which these works extend from, and depend on, his doctoral dissertation, “On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason” — a work that lays out his basic epistemological innovations (as well as his Kantian pedigree), and thus serves as the foundation for his entire oeuvre.

Unlike Kant, Schopenhauer did not hold that all knowledge was strictly representational (i.e., a combination of subject and object). He instead posited that knowledge was divided into a fourfold along two axes: mediated to immediate, and representational to non-representational. Our normal everyday conceptions are mediated by consciousness, and representational. But we can also have:

mediated non-representational knowledge (we directly feel the urges and drives of our bodies in a way that obviates subject/object representational divisions, albeit temporally, and thus mediated by consciousness),

immediate representational knowledge (we immediately feel the atemporal Platonic Forms within music and art without cognizing them first, even though they themselves, and the music and art they stem from, are representational),

and, for the select few, immediate non-representational knowledge (the immediate, intuitive, world-crumbling, self-abnegating insight into the essence of reality that in a sense combines both the subject/object-melting insights into the body-essence as will as well as the non-mediated confrontations with the Platonic Forms — in other words, the lightning-bolt insight into the ultimate unity and essence of reality as the a-rational, a-temporal, voracious, insatiable, self-devouring Will-to-life).

Tracing the details and intricacies of these forms of knowledge, their relationships to Kant’s own epistemology, and their foundational connections to Schopenhauer’s various philosophies falls well beyond the scope of this summary book review — and in fact, would lead me to reiterate Auweele’s entire book itself (and poorly at that). However, it is important to note here that, thanks to his epistemology, Schopenhauer succeeds, like many of his contemporaries, in extending Kant’s transcendental idealism while simultaneously overcoming Kant’s metaphysical agnosticism. In Auweele’s own words:

Most post-Kantian philosophers accepted Kant’s argument that the mere interconnection of abstract thought could not justify the extension of abstract though to existence. There emerged accordingly a need for a ‘mediator’, something that enables abstract thought to love beyond itself. For Fichte and the early Schelling, this was intellectual intuition; for Jacobi, this was the revealed, immediate certainty that God exists as a being outside the self; for Hegel, this was the historical process in which absolute spirit manifests itself; for the later Schelling, this was the immediate epiphany of God in mythology, revelation and art… Schopenhauer’s metaphysics seems to fit with the general post-Kantian philosophy since, on the one hand, he accept Kant’s transcendental idealism and epistemology more or less unabridged and, on the other hand, he argues that we nonetheless have knowledge of the in itself. The decisive difference between Schopenhauer and his contemporaries relates to the type of knowing (which for Schopenhauer is irrational) that could move the agent beyond self-enclosure.

In addition to his Kantian epistemological heritage, Schopenhauer also shares (and radicalizes) Kant’s pessimistic anthropology. Kant found, at the heart of humanity, one indisputable essence, and one ineluctable fact. The essence is autonomy — a complex Kantian concept in itself, but which, for our purposes, we can grossly simplify to free will. But the ineluctable fact is…

… the “propensity to evil”, the “depravity of the human heart” or “radical evil”. He calls this evil radical, not because it is particularly egregious, but because it goes to the ‘root’ (radix) of human nature. This means that evil “corrupts the ground of all maxims” and, on the other hand, “cannot be extirpated through human forces.”

What’s worse, Kant posited a causal connection between the two: we are evil because we have the freedom to be. Schopenhauer’s contemporaries found Kant’s assertions here deeply troubling. And all of them, save Schopenhauer, ridiculed or just flat out ignored Kant’s pessimistic take on human nature. Instead of holding human nature as evil and irredeemable, they chose instead as their Kantian starting points the more optimistic features, like the “normativity of autonomy”, the “architectonics of rationality”, or the “potential hope for self-reconciliation throughout a historical process”. Schopenhauer, however, takes the “deep recalcitrance towards rationality and morality in the human will” as his Kantian focal point and “starting point for his philosophical reflections” — and then radicalizes it — or in Auweele’s words, “Schopenhauer’s philosophy is a metaphysicalization of Kant’s notion of self-willed rebellion to rationality.” The details of this metaphysicalization here are fascinating, though also complex for many reasons — not the least of which is that Schopenhauer denies free will, instead holding that all representational reality is conditioned by the principle of sufficient reason, and thus fully causally determined. But one result worth highlighting, and that again differentiates Schopenhauer from his fellow Kantian successors, is that, as a result of his metaphysicalization, “rationality is but an offspring of a blind will to life that tries to cope with existence in all its horror and agony: its postulations are no more than wishful fictions, and not absolutely necessary, universal notions.” In other words, in contradiction to the entire Western philosophical tradition that preceded him, from Socrates to Kant, Schopenhauer denies reason it’s laudatory place in the hierarchy of human being, much less its soteriological potential.

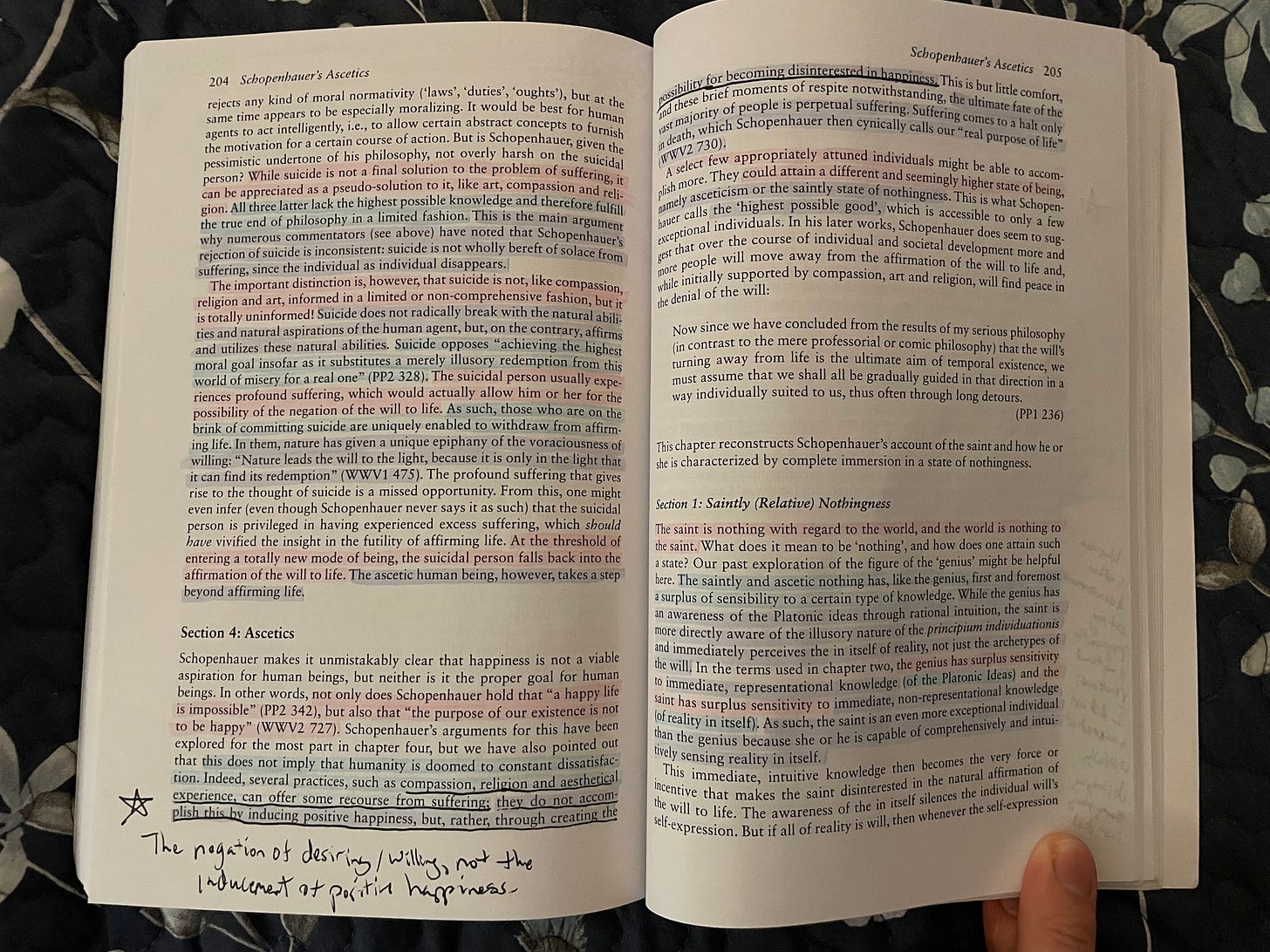

And still, I’ve hardly scratched the surface of Auweele’s magnificent work. After explicating Schopenhauer’s epistemology and metaphysics, Auweele goes on to explore Schopenhauer’s ethics, his philosophy of religion, his aesthetics, and his soteriological ascetics. It’s a fascinating journey through this unique thinkers oeuvre, both in itself and in its interconnections with Kant’s philosophy. And it ends with Auweele’s own thoughtful confrontation with the the deeply troubling implications of Schopenhauer’s philosophy, in which:

“Schopenhauer’s solution to the problem of suffering is trapped within a framework that seems to render all solutions deeply problematic… the denial of the will — the supposedly highest possible achievement of human intellect — is trapped within a pessimistic framework that reduces the potential angelic blare of trumpets usually associated with a highest good to a deafening silence… If this is really the final conclusion of Schopenhauer’s philosophy, then this profound perspective on reality is in dire need of an appendix.”

In other words: bartender, we’re going to need a chaser.